Look . . . Reality is greater than the sum of its parts, and a damn sight holier. And the lives of such stuff as dreams are made of may be rounded with a sleep but they are not tied neatly with a red bow. Truth doesn't run on time like a commuter train, though time may run on truth. And the Scenes Gone By and the Scenes to Come flow blending together in the sea-green deep while Now spreads in circles on the surface. (Bantam 1965 ed., p.14)Here's a little self- referential snippet I was excited to find: Leland Stamper, the emotionally unstable academic, recalls his mother's suicide, then remarks dismissively, "Besides, there are some things that can't be the truth even if they did happen" (p.70). Compare Leland's statement to Chief Bromden's famous claim about his visions in One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest: "It's the truth even if it didn't happen."

It's been almost a year now since I graduated with a B.A. in English and Philosophy. I can still remember exactly how I felt that night after commencement--like I hadn't spent as much time as I should have on anything, hadn't poured my heart and soul into anything. Sure, I chose my majors and I loved them, but I wished I had spent more time reading just because I was interested, or that I had written an essay weeks in advance because I was so excited about the subject. It seemed that even when I was studying something I loved, I became bogged down in the day-to-day, and the rules and rigor of academia too quickly drained my enthusiasm for literature. As Leland is discussing his college days with Viv, his seductee-to-be, he expresses some of the same sentiment I felt:

"Lee, if it isn't prying . . . was it always dull, your studies? Or did something happen to take the life out of it?" . . . .I do miss the days where I could always say, "I'll do it tomorrow. I'll research tomorrow. I'll write tomorrow. I'll reach literary nirvana sometime Tuesday evening." And then all of a sudden my tomorrows were gone, I was done with school, and I had not only no more tomorrows but nothing to postpone. Sure, I don't get up at four-thirty, but I do find myself doing the same thing one day as I did the day before, without really considering the search for my personal Valhalla. This blog is an attempt to make use of my todays and tomorrows and to recover my enthusiasm for literature before re-entering the academic world.

"No, it wasn't always dull. Not at first. When I first discovered the worlds that came before our world, other scenes in other times, I thought the discovery so bright and blazing I wanted to read everything ever written about these worlds, in these worlds. Let it teach me, then me teach it to everybody. But the more I read . . . after a while . . . I began to find they were all writing about that same thing, this same dull old here-today-gone-tomorrow scene . . . Shakespeare, Milton, Matthew Arnold, even Baudelaire, even this cat whoever he was that wrote Beowulf . . . the same scene for the same reasons and to the same end, whether it was Dante with his pit of Baudelaire with his pot: . . . the same dull old scene . . . "

"What scene is that? I don't understand."

"What? Oh, I'm sorry; I didn't mean to come on so jaded. What scene? This one, the rain, those geese up there with their hard-luck stories . . . this, this same world. They all tried to do something with it. Dante did his best to build himself a hell because a hell presupposes a heaven. Baudelaire scarfed hashish and looked inside. Nothing there. Nothing but dreams and delusion. They all were driven by the need for something else. But when the drive was over, and the dreaming and the deluding worn out, they all ended up with the same dull old scene. But look, you see, Viv, they had an advantage with their scene, they had something we've lost . . . .

"They had a limitless supply of tomorrows to work with. If you didn't make your dream today, well there was always more days coming, more dreams full of more sound and fury and future: what if today was a hassle? There was always tomorrow to find the River Jordan, or Valhalla, or that special providence in the fall of a sparrow . . . we could believe in the Great Gettin'-up Morning coming someday because if it didn't make it today there was always tomorrow."

"And there isn't any more?"

I looked up at her and grinned. "What do you think?"

"I think it's pretty likely . . . that the alarm will go off at four-thirty, and I'll be down making pancakes and coffee, just like yesterday." (Bantam 1965 ed., p.414-5)

Ah, poor Kesey. He lost the respect of the his fellow scholars when he stepped outside the bounds of fiction into the world of drug-induced art and poetry. Sure it may have worked for Coleridge, but Kesey lived in a different era. His reputation as a literary giant was unfairly maligned for the publication of the following fascinating works:

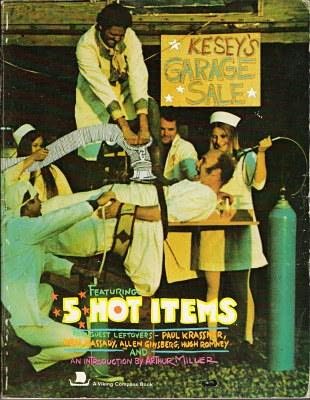

Kesey's Garage Sale. There's a signed first edition of this on Amazon for $300. Would someone buy it for me?

I saw this at City Lights Books and was absolutely mesmerized by the art. Kesey went from Stanford writing student to psychedelic activist in a matter of a few years. Did LSD expand his mind or simply warp it? The debate continues.

Your Ginsberg-of-the-day: [From Howl]

"who threw their watches off the roof to cast their ballot

for Eternity outside of Time, & alarm clocks

fell on their heads every day for the next decade"

No comments:

Post a Comment